The Sun King

The Weekend Australian

10 - 11 September 2016

Ashleigh Wilson

John Olsen leans over his desk, charcoal in hand. Shadow falls over the

paper as he presses down, drawing a line from top to bottom and then

sending it curling in different directions. His hand moves with a slow,

deliberate rhythm, and he adjusts the angle of the charcoal to vary what

he calls the pace of the line. It’s a picture of a pelican, but it’s

also a demonstration of positive and negative space, male and female,

the perfect balance between the yin and the yang. “It’s the idea of the

emptiness being as full as the fullness,” he says.

Behind him stands a

large unfinished painting of Lake Eyre. It’s a work unlike anything he

has done before. This picture won’t be included in his upcoming

retrospective in Melbourne and Sydney, but he seems deeply satisfied

with its progress. With this painting, Olsen says, he is edging closer

than he ever has to Lake Eyre after wrestling with the subject for many

years. “I just had this notion of extending my experience with it.”

At

88, Olsen has a secure hold on the crown as Australia’s greatest living

painter. His work commands great respect, and he’s as close to a

household name as an artist could be. In recent years he has enjoyed a

flurry of honours, from a belated Archibald Prize in 2005 and his

elevation as life governor at the Art Gallery of NSW to two honorary

university degrees. He also added an Order of Australia to his title of

OBE.

This weekend he will travel from his home in NSW’s southern

highlands to Melbourne for the opening of a career retrospective at the

National Gallery of Victoria. The show has been put together in tandem

with the AGNSW, where it will open next year. The two galleries hosted a

retrospective of his work 25 years ago, so this exhibition is a story

of longevity, if nothing else. Certainly it’s hard to think of another

living Australian artist bestowed with two major retrospectives a

generation apart.

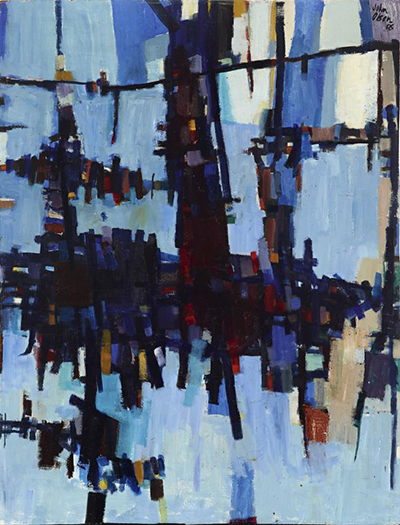

John Olsen's Dry Salvages (1956), named after a TS Eliot poem.

Earlier this week Olsen invited Review to his property just

outside Bowral, a 90-minute drive from Sydney and home for the past five

years. Its energy centre is his studio, a vast, light-filled space just

a few steps from his bedroom and overlooking a lake where ducks make

circles on the water. Here he sat, surrounded by paints, canvases,

brushes and books, and discussed his creative practice, his world, his

high-profile children (Tim is a prominent Sydney gallerist; Louise

co-founded Dinosaur Designs) and the passing of time.

Invited to

consider the artists no longer with him, he sighs: “Drysdale was a good

friend of mine. Nolan gone, Whiteley gone, Lloyd Rees gone. They’re

nearly all gone.”

A retrospective is an opportunity for

reflection, and Olsen is happy to oblige. There’s much to cover: the

time he protested a conservative Archibald Prize; his affection for

Spain; the heady atmosphere on his return to Australia; his Opera House

mural; his exploration of the Australian landscape; his relationship

with younger artists. He’s great company, too, charming and erudite and

witty, qualities that shine through whether he’s enjoying a long lunch

at Lucio’s restaurant in Sydney or talking about art in his studio.

But

Olsen is busy with new ideas, so there’s only so much time he can spend

looking backwards. Apart from the Lake Eyre picture, which is still

taking shape, another commission awaits his attention, a picture that

will take him back to the beginning of his own story. It’s a meditation

on Newcastle, the city of his birth.

'Where is humanity without poetry? In a terrible heap'Naturally

enough, for Olsen, that picture has its foundations in poetry. Its

title is The River is a strong brown god, a line from TS Eliot’s Dry

Salvages. As it happens, he used the title of the same poem in 1956 for a

painting in Direction 1, a show at Sydney’s Macquarie Galleries and a

breakthrough moment for the young artist. So perhaps this is a time for

both reflection and renewal, a time when the recurring patterns of the

past come into view.

“I’m finding I’m working slower at the moment.

Maybe I’m getting old.” Olsen looks up from his TS Eliot and continues

in a whisper. “I don’t feel it.”

Of all the many loves in Olsen’s life, one constant companion is

poetry. Eliot is a favourite, of course; he’s currently enjoying Peter

Ackroyd’s biography of the artist. He also loves WB Yeats, WH Auden,

Dylan Thomas, Stephen Spender and Gerard Manley Hopkins — from whom the

line “nature is never spent” seems especially apt, considering Olsen’s

tenderness towards the natural world. During our conversation, Olsen

jumps up several times to retrieve a book of poetry from the shelf to

illustrate a point. He’s also fond of quoting lines committed to memory.

One passage he has been quoting to others for some time comes from the

opening of Pied Beauty, by Hopkins:

Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow …

“Where

is humanity without poetry?” Olsen says. “In a terrible heap. That’s

one of the problems we have in Australia, and I guess this could be

extended to anywhere in the Western world, where poetry is very badly

taught in schools. If I was teaching poetry I could tell you that the

kids there would really, really be moved by it. But it’s passed off as

something that no one understands.”

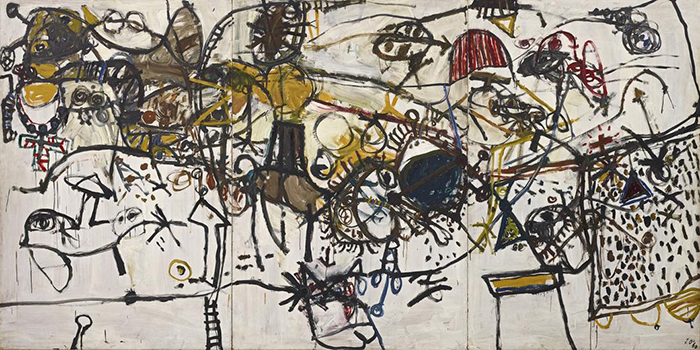

Olsen painted Spanish Encounter (1960) in a five-hour burst on his return to Australia .

It wasn’t until Olsen travelled to Europe in the late 1950s that

he felt he really learned to harness the power of poetry. He ended up in

Majorca and fell in with the poet Robert Graves, who helped him find

focus.

“He was very good. He said that when you look at an object,

always consider its metaphorical extension. Now that was very

valuable.”

Olsen turned to poetry for one of his best-known

commissions, a work that continues to look over Sydney Harbour to the

north. It was late in 1971, two years before the opening of the Sydney

Opera House, when James Gleeson invited him to create a mural inside the

new building. Gleeson, a critic, artist and chairman of the Dobell

foundation, had been impressed by Olsen’s Spanish Encounter, a vigorous

three-panel epic that Olsen had painted in a five-hour burst on his

return to Australia a decade earlier.

Olsen decided to base the mural on Five Bells, an elegy by

Kenneth Slessor for a friend who had gone overboard in Sydney Harbour

with beer bottles in his pocket. The artist sought out Slessor, who told

him the story behind his poem, and then set to work.

“As a

young man,” Olsen says, “I was very excitable and very haptic and all

over the place. Talented, but all over the place. I just don’t feel that

anymore. I think I came close to that feeling with the Opera House.”

While

the mural will not be included in the retrospective, an earlier work,

Five Bells, will be put on display when the show travels to Sydney.

Olsen remembers the mural’s creation as a difficult period, how some of

the workers heckled him as it was coming together. But four decades on,

he thinks the picture, initially conceived as a ceramic, has aged well —

even if he’s no fan of the purple carpet in front.

Did he ever

doubt himself? “Never for a moment. Never. And we spent a lot of time

getting that purply moonlight colour, because it was important to the

theme.”

The new retrospective, jointly curated by David Hurlston and

Deborah Edwards, senior curators at the NGV and AGNSW respectively,

will present a spread of Olsen’s career, from paintings to ceramics,

tapestry, prints and drawings. Compared to the earlier retrospective, in

1991 and 1992, Olsen describes this show as a “proper summary” of his

career. There will be 108 works in total, covering six decades of work.

It

must be tempting to look back over it all and wonder what could have

been done differently. “I don’t think of perfection, because that drives

you nuts,” Olsen says. “When you’re thinking of perfection you might be

thinking of somebody else’s idea of perfection. Leonardo da Vinci’s

idea of perfection, that would have nothing to do with Rembrandt’s idea

of perfection. Perfection looks after itself.”

The title of the

show is The You Beaut Country, a reference to the series created

following his return to Australia. Olsen says the phrase draws on his

experience in Spain in the 50s — “completely isolated and very, very

poor” — and the contrast with Australia, where everything felt so

“magically alive”. It also relates to the “commitment of innocence” that

Australia had taken to Gallipoli.

“So I think that the ‘you beaut country’ has that kind of

innocence about it,” he says. “That first reaction was a reaction

against Spain’s civil war, and the contrast between coming back to

Australia. It was an extraordinary thing: it was a Saturday night. The

ship came in, there was the showboat, and there was raucous saxophone

music and the whole harbour was dancing. I didn’t have any notion of

doing the ‘you beaut country’ then, but it seemed to me to be an idea of

a contrast. A parallel to Australia’s enthusiasm.”

From this

point, Olsen travelled widely across Australia. He took in the likes of

Lake Eyre, Lake Hindmarsh, Arnhem Land and Bass Strait, and he speaks

with enthusiasm about a country that he insists is best viewed from the

air, and the great empty spaces that are anything but empty. Most

Australians, he says, cling to the edges of their country. He calls it a

“saucer-like existence”.

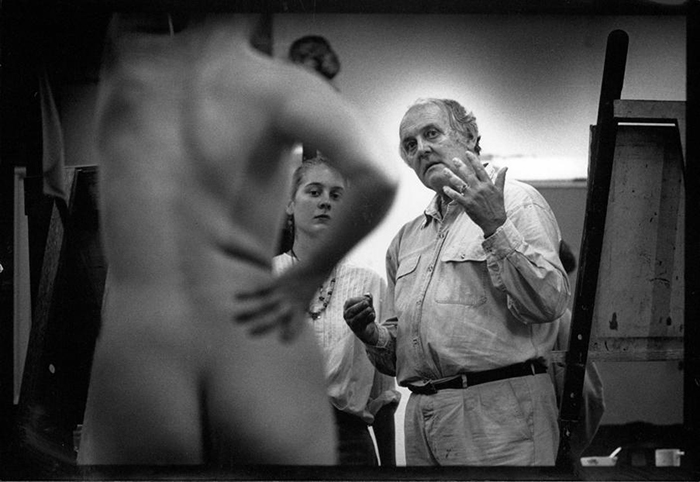

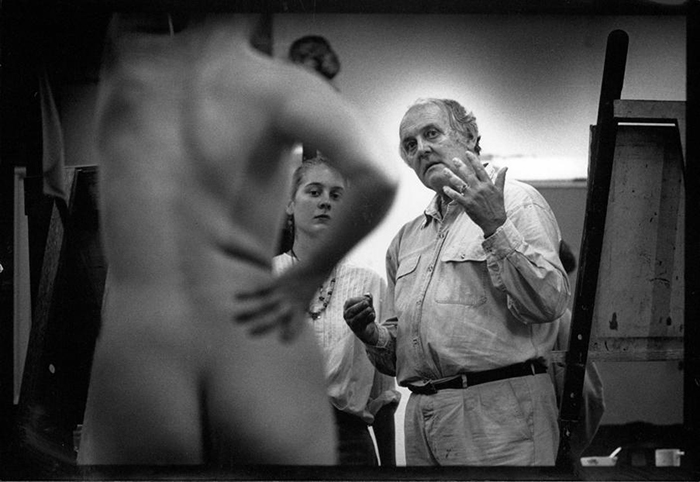

John Olsen at work earlier in his career.

John Olsen at work earlier in his career.

“It’s so big and so chaotic, unlike the European landscape, which

is ordered, and honed and manicured by great poets,” he says. “The

Australian landscape is like a dog’s hind leg — and that’s the value of

Sidney Nolan. His landscapes revealed for the first time the essential

untidiness of the Australian landscape.

“But the investigation goes further. When you begin to travel over the top of it, then it begins to explain itself.”

Ben

Quilty, an admirer and a friend, a fellow Archibald-winning artist who

lives nearby in the southern highlands, identifies a life-affirming

quality that Olsen brings to all his paintings.

“The thing about

John is that he always brings it back to a very romantic, incredibly

optimistic form of visual language,” Quilty says. “Which kind of goes

against the pessimistic nature of discussion about contemporary society

and the world and politics. That’s about really the heart of what

John’s work is about. The joy of being alive.”

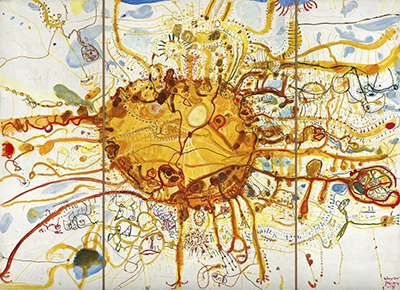

Olsen's Sydney sun (or King Sun) (1965).

In recent times, it feels like Olsen has been everywhere.

Darleen Bungey’s biography was published in 2014, followed the next year

by an Olsen book about the Opera House mural. Last month came the

publication of Buns in the Oven, detailing Olsen’s brief stretch running

an art school in Sydney, and next month the AGNSW will publish an Olsen

recipe book. And the twin-city retrospective will be followed by a

separate show at the Newcastle Art Gallery called The City’s Son. “It’s

very exciting,” he says, “but it’s very exhausting too.”

There is

good cause for Olsen to be distracted: his wife of 27 years, Katharine,

has just received treatment for a brain cancer. Olsen says the renowned

neurosurgeon Charles Teo led the operation, and she is now recovering

back at home. “She’s doing well.”

As soon as he returns from

Melbourne, Olsen will start work on his Newcastle commission. He has

plenty of ideas: there’s a notebook filled with sketches of the city and

its industrial complexion, as well as Eliot’s words about the strong,

brown river god, sullen, untamed and intractable. “I’ve got an affection

for Newcastle,” he says, “a great affection.”

Does he fear running out of ideas? Olsen points to the Lake Eyre

painting in progress against the wall: rivers snake to the sea, a blue

expanse framed by the legs of Mother Earth, all rushing together with

that inimitable Olsen sense of line and colour.

“Just look at

that. That’s entirely different to any interpretation I’ve done of Lake

Eyre. And it’s reinforced by a better philosophical attitude.”

The

artist leans back in his chair. A moment passes, and the conversation

turns to the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, whose poem Ithaka encourages

attention on the journey rather than the destination.

“It’s the travelling through,

you see,” he says. “There’s a way of painting — Jeffrey Smart did it

this way — in which you do a very detailed small work and you scale it

up and transfer it on to a canvas.

“To my mind, I only have a

theme and I concentrate on where I am, whether it’s Lake Eyre or Sydney

Harbour. I’m travelling, but I don’t know where I’m going to finish.”

John Olsen: The You Beaut Country

is at the National Gallery of Victoria from September 16 to February

12; then at the Art Gallery of NSW from March 10 to June 12.

John Olsen: The City’s Son is at the Newcastle Art Gallery from November 5 to February 19.

Read full article here - http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/review/john-olsen-retrospective-at-ngv-reveals-poetry-in-his-palette/news-story/962ae0a947cfab0ebc1723795a5d6ebc

_back to previous page

John Olsen at work earlier in his career.

John Olsen at work earlier in his career.