Beyond the Veil at Olsen Gruin

Arte Fuse 9 June 2018

Jonathan Goodman

_view full article online_view related exhibition

‚??Beyond the Veil‚?Ě curated by Adam Knight at Olsen Gruin, installation view.

"Beyond the Veil," the inspired group show at the Lower East Side gallery Olsen Gruin, looks at the metaphysical dot paintings of several aboriginal women, many of them made when the women were elderly-some seventy-five years or older. The metaphysics of this work, while of course consistent with the artists themselves, couldn't be more different from that of the mostly Western visitors to the show. There is a kind of dreaming here we just do not come across in the arts of our cultures. It is codified, seemingly abstract and asserts an intuitive intelligence that is enabled to a remarkable extent, so its intuitive structure might well be called a dream culture. This would be a powerful antidote to certain problems in current Western culture. Contemporary art in New York needs a language that posits spiritual values that are different from America's pursuit of an artistic, psychological and financial reading of culture-even if it takes an effort beyond the usual to address and support that language.

‚??Beyond the Veil‚?Ě curated by Adam Knight at Olsen Gruin, installation view.

So, there is something that holds true in a show like this, which presupposes a different way of looking at society because of the long reach of the West‚??s current obsession with money. Clearly, affluence is not a major interest of the women in this show, who live in the central desert of Australia and who work on paintings that, despite their abstraction, remain close to their lives. This is a different cry by far from the recent dot paintings of Damien Hirst, whose probable appropriation‚??we are not certain this is true‚??looks like very much like the theft of a venerable art coming from a culture some 100,000 years old. Hirst‚??s borrowings do tend to look facile in light of the greater gravitas of the indigenous women‚??s works, which can be understood by Western viewers‚??albeit on a level likely more superficial than the paintings themselves. In any case, the controversy raises real issues about the appropriation of other cultures‚??a hallmark of Western art practice since the beginnings of modernism, when Picasso made use of African masks for his work Les demoiselles d‚??Avignon.

It does feel like the metaphysical perception of this group of works is beyond the way we see the paintings. How are we to make sense of a belief system so different from our own? Some of the imagery can be explained‚??for example, the presence of a U-shape in a painting indicates a similarly shaped depression made by a woman sitting in the sand‚??in this case, likely the artist herself. So, we are hard put to fully grasp the art as it truly is (although it is necessary to try to do so). If it is, in fact, difficult to impossible to read this work on its own terms, our recasting it into a Western formalist reading isn‚??t effective and may well be damaging. But, given the gap between indigenous Australian culture and the New York art world, that may be all a Western audience can do, given the spiritual complexity of the art and, likely, the lack of knowledge about such art in New York City. The ethics addressing this position must be much higher than the commercial interests the New York art world may be used to. This is because the art, which seems so alive in a contemporary way for us, is actually a repository of spiritual insight developed thousands upon thousands of years ago. The esthetic involves a sense of time beyond that which we can conceive of. By extension, it presupposes an ethics we might well learn from.

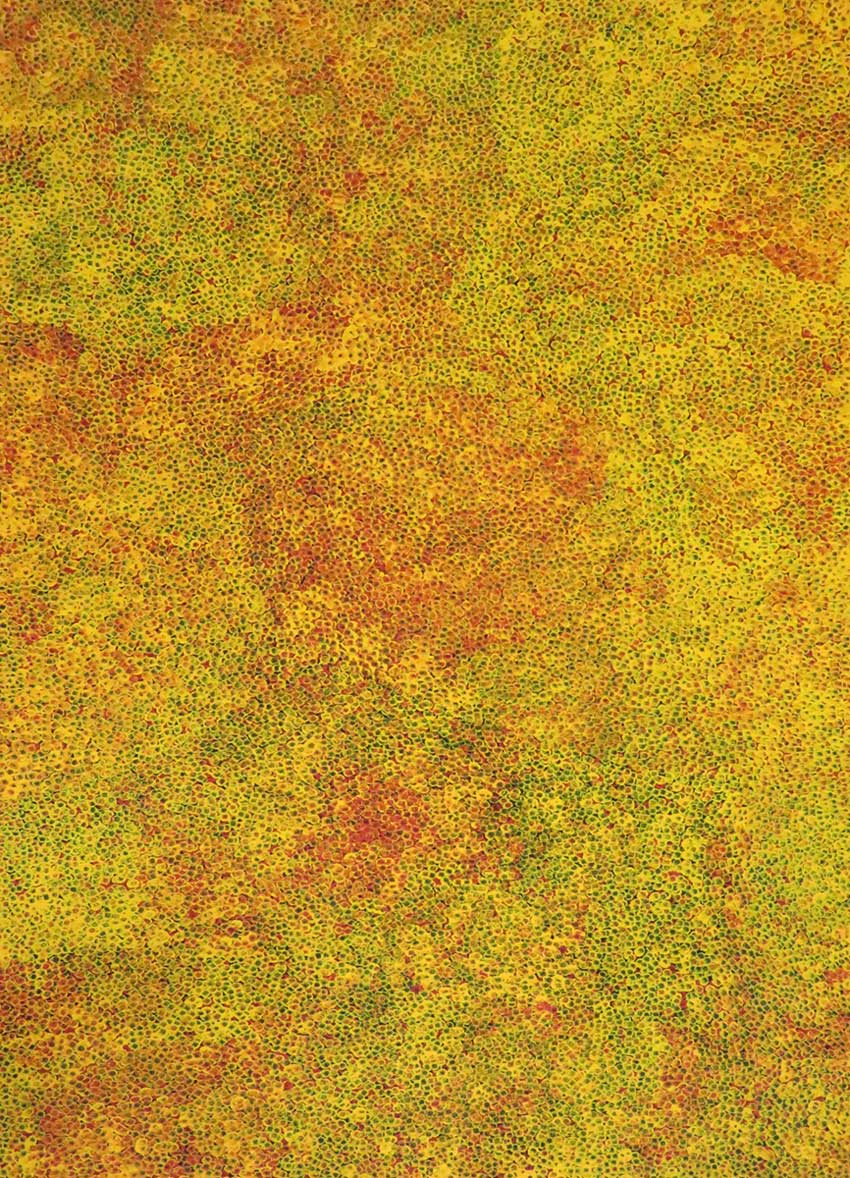

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Untitled 1991, synthetic polymer paints on Belgian linen, 58.8 x 35.2 inches (149.4 x 89.4 cm).

A favorite painter in this very worthy show is Emily Kame Kngwarreye, an artist whose larger focus is the celebration in which she lived. The artist is particularly oriented toward the use of small dots. Her piece, untitled and made in 1991, consists of a large rectangular plane, oriented vertically (it is also possible to place this work and the others in any orientation one wants), painted yellow but covered throughout with evenly spaced small dots of bright colors. The result is an image of both freedom and restraint, as indicated through by the artist‚??s style, which is both tight and freely handled. The dots in Gayla Pwerle‚??s 2015 painting Bush Tomato are clumped together in different color groups. Together, over time, the groups of dots result in an abstract painting of remarkable beauty, which we would consider abstract were it not for the painting‚??s title and the bright red color, akin to the red of the tomato, used throughout the piece. So, it becomes clear that the paintings are widely seen as abstract works of art, but in fact, their reference is larger, more representational, and more deeply linked to the artist‚??s culture than we would think.

Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi, Grandmother‚??s Country, 2017, Synthetic polymer paints on Belgian linen, 67 x 60 inches (170.2 x 152.4 cm).

The painting by Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi is a riot of colors and patterns made from repeated dots. Her works consist of U shapes indicating women sitting on the ground, flowers near water and rock, sharp swamp grasses, emu eggs and bush turkey eggs. These particular images result in a broad and complex array of images, which seem to Western eyes to participate in a broad spectrum of abstraction but which actually represent specific images in nature. The intricacy of the painting is stunning‚??in the manner of a tapestry, coils of jewel-like beauty enter into a conversation with what look like streams. One‚??s gaze follows the allover pattern of the imagery. Nungurrayi has a quick and insightful knowledge of the symbolic aspects of nature. Bush Yam (2015) by Evelyn Pultara consists of bunches of dots, mostly white and mauve and orange, that abstractly detail the bush yam, a staple food of the indigenous artists in Australia‚??s central desert. The dots accumulate, and for the unknowing viewer, look very much like they support an essentially abstract painting. But this is not the case: Pultara is representing a real object‚??an item of food key to the food economy of the artist‚??s people. So the work is not merely a conglomeration of dots, as the very superficial duplications of Hirst suggest. The challenge for the Western audience is to see the paintings on the artist‚??s terms rather than its own.

Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin, Antara 2016, synthetic polymer paints on linen, 78.5 x 58.5 inches, (199.4 x 148.6 cm).

Antara (2016), by Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin, looks very much like a landscape viewed from above. It looks as if the painting is composed of furrowed rows in an array of colors‚??orange, yellow, blue. These patterns are regularly punctuated by circles consisting of layers of dots. The painting is structured beautifully, in a manner it is fair to call rational, although clearly, the work is making use of methods far beyond an analytical approach. The problem for the art writer attempting to interpret these paintings accurately has very little to do with acknowledging their intense, self-evident beauty. Instead, it is the need to make sense of symbolic implications in the works, which amount to a real language, however ethereal it might seem to someone unfamiliar with Australian indigenous art. This means that we must intuit the works as best we can, as well as do research into the particulars of the vernacular being used. At the same time, it seems of little practical use to pronounce these works as existing entirely outside our ken. There is a spiritual language that holds sway in this art, and this is recognizable even to those uninitiated to the specific meaning being adumbrated in the paintings. But just as the hieroglyphs were deciphered, so we can make advances into the particulars of what we see. Goodwin‚??s language is hardly occult, but it is intuitive, symbolic, and spiritual‚??qualities not much taken up in contemporary Western art!

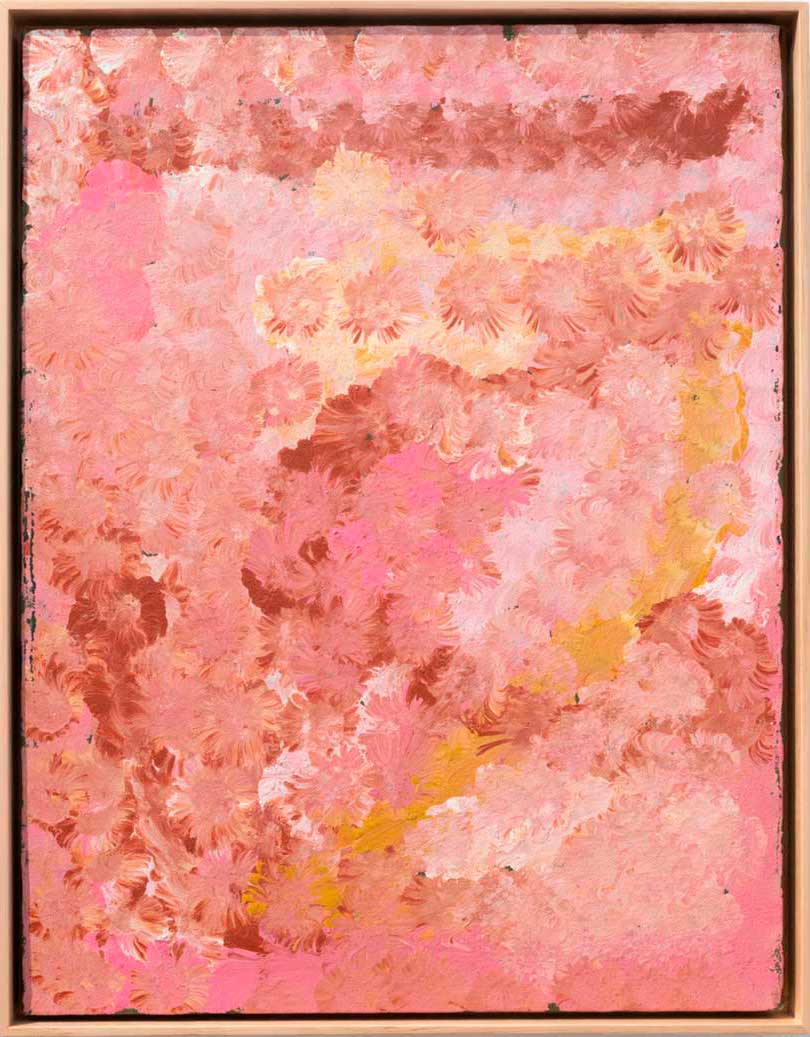

Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Wild Flower Dreaming 1994, Synthetic polymer paints on Belgian canvas, 13.8 x 17.9 inches (35.1 x 45.5 cm).

In a number of ways, Wild Flower Dreaming (1994), Kngwarreye‚??s pink study of wildflowers, comes closest in this show to an image Western viewers can easily understand. Painted in a light pink, the work presents individual flowers that are tightly spread across the canvas, in a way that suggests a density of growth and beauty we might experience in a meadow far away from the central desert in which the artist worked. The composition, which is extremely beautiful, shows us that a botanical appreciation is not limited to any culture at any time or place. Indeed, the pleasure derived from viewing this particular piece makes it clear that the Australian aboriginal artist felt perfectly comfortable in rendering the flowers as flowers, without incorporating them within the body of her intricate belief system. The painting‚??s beauty should act as both an encouragement and a warning‚??namely, that the range of the Aboriginal female artist is as broad as our own. If in this show, the artist‚??s Western audience is baffled by intimations of spiritual insight the West has no contact with, it makes sense that the viewer would endeavor to learn the idiom‚??and the import‚??of what she says. At the same time, it also makes sense for these remarkable artists‚?? audiences to acknowledge the breadth and geographical reach of the paintings. We can begin by appreciating and then develop a greater sophistication by study. As a result, it isn‚??t a mistake to acknowledge the work as abstract, although this statement is not nearly as sophisticated as the art. It is likely best to suspend our disbelief in this wonderful show, first to simply appreciate and then to find out as much as we can, so we can enjoy the work on the artists‚?? terms rather than our own.

Participating Artists: Emily Kame Kngwarreye, Tuppy Ngintja Goodwin, Evelyn Pultara, Gabriella Possum Nungurrayi, Gayla Pwerle, Polly Ngale, and the Women‚??s Collaborative comprising Beverly Cameron; Kathy Marinkga, Imitjala Curley, and Tjangili George.

BEYOND THE VEIL CURATED BY ADAM KNIGHT

May 16 ‚?? July 8, 2018

OLSEN GRUIN NY

-Jonathan Goodman

Images courtesy of Olsen Gruin and the Artists.